442nd Regimental Combat Team coat of arms

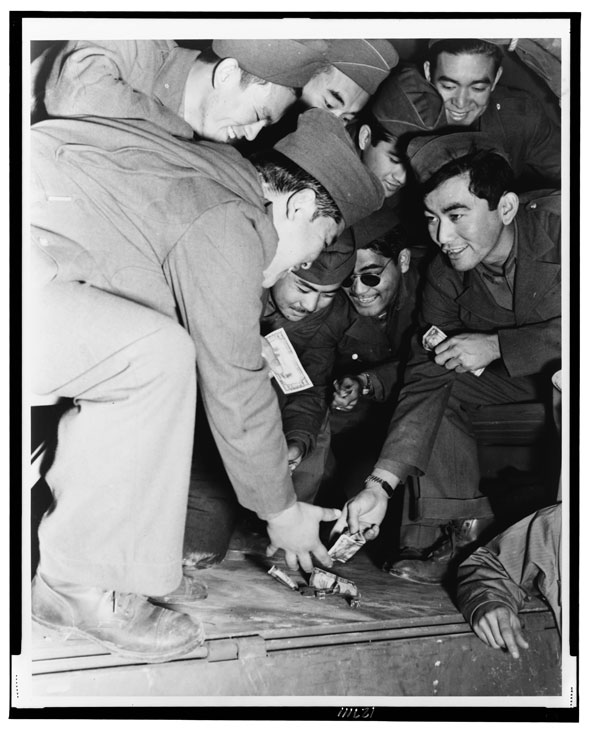

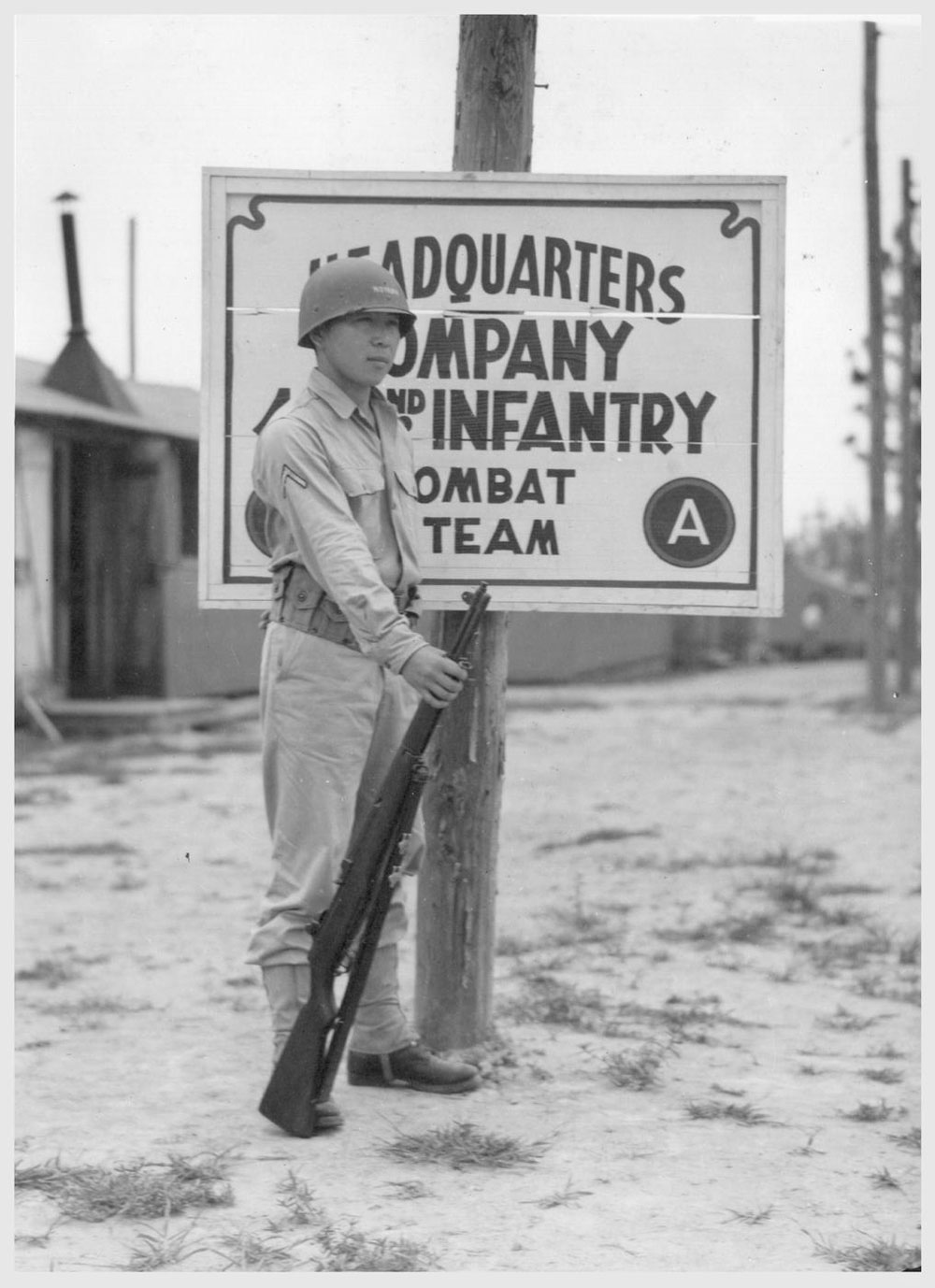

“Go For Broke” was the motto of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an Army unit comprised of Japanese Americans from Hawai’i and the mainland United States. The motto was derived from a gambler’s slang used in Hawai’i to “go for broke,” which meant that the player was risking it all in one effort to win big.1 The player would put everything on the line.

It was an apt motto for the soldiers of the 442nd. As Nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans, and American-born sons of Japanese immigrants during World War II, they needed to put everything on the line to “win big.” For these Nisei, they were fighting to win two wars: the war against the Germans in Europe and the war against racial prejudice in America.