A Different Type of Battle- Home

- History

- Conflict History

- A Different Type of Battle

- Home

- History

- Conflict History

- A Different Type of Battle

The Fight against Unjust Treatment at Home

While the Nisei soldiers were fighting overseas, other Japanese Americans fought a different – but just as courageous – battle on the home front. Their fight was against unjust and discriminatory treatment. They did not battle with guns and hand grenades, but with words, legal cases, brave moral stands, and the strength of their convictions. Many faced prison time, threats of execution, and lifelong stigma for the stands that they took. Still today, many have not recognized the courage of their actions, as their stories have often been suppressed.

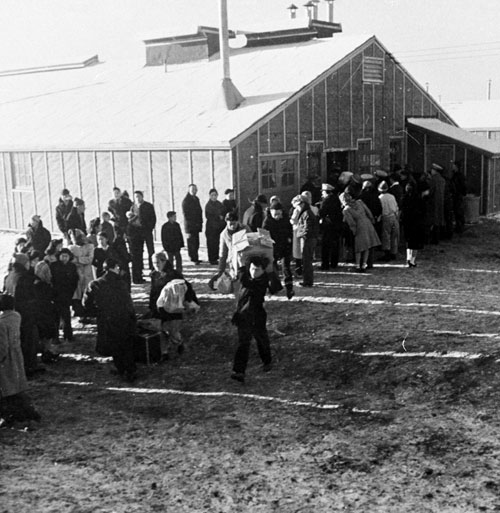

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and America entered World War II, the American government took strong – and in many cases unconstitutional – discriminatory action against those of Japanese descent living on her shores. About two-thirds of these Japanese individuals were American-born citizens. On the mainland, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, resulting in the forced relocation of 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes and into incarceration camps surrounded by barbed wire.

Japanese Americans were declared ineligible for military induction, and those already in the Army were assigned humiliating non-combat duties on inland bases. Later, while still imprisoned in incarceration camps, Japanese Americans were again made eligible for military service and eventually the draft. Thus, young Nisei men faced the following set of circumstances: they were humiliated and told that they could not serve their country; they were forcibly removed from their homes and imprisoned in a barbed wire camp; and then, while still imprisoned, they were told that they were again eligible for the draft and were required to sacrifice their lives if needed in the Army of the government that had imprisoned them.

It is no wonder that many Japanese Americans dissented in one way or another. Some resisted the draft, some started legal cases that went all the way to the Supreme Court, some renounced their US citizenship, some refused further military service, and many voiced their concerns in their answers to a controversial “loyalty questionnaire.” The many ways in which Japanese Americans resisted are far too numerous to count, and each decision – and each method – was highly personal to each individual who took the courage to dissent. Furthermore, each person who dissented knew that they would face retribution from the government and other Americans, and even ostracism from their own families and friends in the Japanese American community. Dissenters were stigmatized as “troublemakers,” and their moral stances often tore their families apart.

This website does not go into depth about the individual dissenters and the wider history surrounding their actions. However, the Japanese American World War II story – and the experience of the Nisei soldiers – cannot be told without addressing the courageous actions of those men and women who “fought” on the home front through their moral resistance. They were risking their lives and reputations to make America, and her Constitution, stand for what the Founders truly envisioned: a land of liberty, equality, tolerance, and opportunity. They fought for civil rights ten years before Rosa Parks sat down on a Montgomery bus and twenty years before Martin Luther King Jr. spoke eloquently of his dream. Their courage must always be remembered.

The Supreme Court Cases

Four Japanese Americans legally challenged the government’s discrimination all the way up to the Supreme Court. Gordon Hirabayashi, a student at the University of Washington, challenged the curfew and exclusion orders imposed upon those of Japanese descent. Fred Korematsu also challenged the exclusion orders, refusing to leave his home to be sent to camp. Minoru “Min” Yasui, a lawyer, made himself a legal test case to challenge the curfew orders. Mitsuye Endo, a young Nisei woman, challenged her forced removal by the government.

Hirabayashi, Korematsu, and Yasui all lost their cases, while the court decided in Endo’s favor. However, even in Endo’s case, the court refused to address the constitutionality of the exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans. While the court would decades later amend some of the wrongs, the four individuals were long seen as legal “troublemakers” rather than the brave Americans that they truly were.

Voluntary Evacuees

For a small window of time in 1942, some Japanese Americans were given the opportunity to voluntarily move away from the West Coast and avoid incarceration. Although this may not seem like a form or “resistance” or “dissent,” it was indeed a courageous action taken by those who wished to avoid the unjust governmental orders. Many left family, friends, and homes for life in a completely new place.

Military Resisters

Some Japanese American soldiers, many of whom had been in the Army before Pearl Harbor and had been mistreated since, resisted while in the military. Most of these men had been loyal soldiers, but had reached a boiling point after unending mistreatment of both them and their families. One group of 21 men, who came to be known as the Fort McClellan Disciplinary Barrack Boys, refused further combat training after enduring recurring unjust treatment. Many of these men had been humiliatingly kept under armed guard during a visit by President Roosevelt to their base at Fort Riley. When the men later were transferred to Fort McClellan and refused combat training, they were court-martialed, dishonorably discharged, and sent to prison.

Another group of men, who came to be known as the Camp Grant Eleven, also refused to serve overseas. While serving honorably at Camp Grant, the Nisei soldiers had been the focus of inflammatory racist statements made in a newspaper by a New Jersey congressman. This and other mistreatment led the eleven to seek renunciation of their citizenship and expatriation to Japan. They were court-martialed, dishonorably discharged, and confined to prison.

Finally, some Japanese American soldiers were not kicked out of the Army but were placed within a special unit so that the Army could keep a close eye on them. The 1800th Engineer General Service Battalion consisted of American soldiers of Japanese, German, and Italian descent whom the authorities had deemed “troublemakers.” Despite all of the suspicion and prejudice against them, the unit performed magnificently, and even received an honorary citation for their work.

Protesting the Loyalty Questionnaire

In 1943, the government made all adult Japanese Americans in the camps answer what became known as the “loyalty questionnaire.” Two of the questions, numbers 27 and 28, caused the most problems. Question 27 asked if the person was willing to serve in combat duty wherever ordered. Question 28 asked if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. The Japanese Americans in camp wondered if answering “yes” to question 27 would essentially volunteer them for the Army. Question 28 was even more problematic. On the one hand, young Japanese Americans who had never had any allegiance to Japan could not forswear any allegiance that they had never possessed. For their parents, first-generation immigrants who were denied US citizenship, forswearing their Japanese citizenship would essentially leave them stateless. Furthermore, families did not want to be broken up if they answered the questions differently.

All of this made for incredible stress and anxiety. Those who answered “no” to both questions became stigmatized as “No-No’s,” and even those who answered “no” to only one of the questions, left the questions blank, or qualified their answers were seen as disloyal “troublemakers.” Those whom the government deemed disloyal were afterwards moved to Tule Lake, which was transformed into a segregation center. Many of those moved to Tule Lake are still to this day ostracized, despite the courageous stance that they took in a period of extreme stress.

Draft Resisters

When Japanese Americans again became subject to the draft, they were still behind the barbed wire of the incarceration camps. Many Japanese Americans felt that it was unjust to force those imprisoned by their government to serve in its armed forces. Almost 300 young Nisei men thus resisted the draft when their numbers were called. Most ended up serving time in federal prison, and they faced lingering hatred and stigmatization from the larger Japanese American community.

The only organized instance of draft resistance occurred at the Heart Mountain incarceration camp. Sixty-three young resisters were tried and convicted in the largest mass trial in Wyoming’s history. A second group of 22 Heart Mountain Nisei later resisted. Today these 85 men are seen as courageous for their moral stand against unjust treatment.

Renunciants

Late in the war, as the government was hoping to clear the camps, a controversial policy was enacted that allowed Japanese Americans to renounce their US citizenship and expatriate to Japan. Over 5,500 Japanese Americans renounced, many under duress, pressure, or confusion. Most were from Tule Lake. A large number quickly came to regret their decision once they realized all of the consequences it entailed. Over 1,000 were deported to Japan, but thanks to the efforts of attorney Wayne M. Collins, the further deportations were halted and almost 5,000 eventually had their citizenship individually restored by over two decades of exhaustive legal work performed by Collins and Tetsujiro “Tex” Nakamura.

A Different Kind of Courage

The short descriptions above only list a handful of ways in which Japanese Americans resisted unjust treatment during World War II. Dissent was practiced in countless individual ways, both large and small. But common to all was the remarkable courage that it took to make their stand. They envisioned a better America based on the true ideals of equality, and they risked their lives and their reputations to make it happen. While the Nisei soldiers were exhibiting their courage overseas, these men and women were fighting valiantly on the moral home front.