100th Infantry Battalion (Separate)- Home

- History

- Unit History

- 100th Infantry Battalion

- Home

- History

- Unit History

- 100th Infantry Battalion

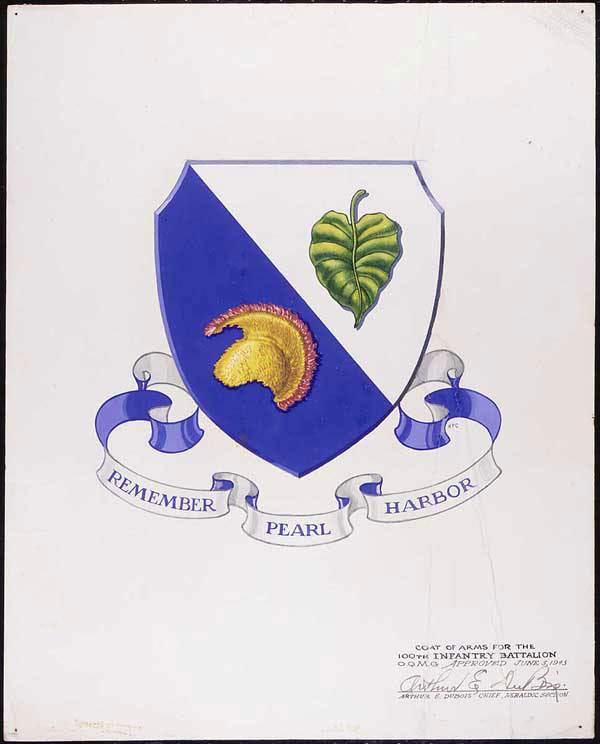

“Remember Pearl Harbor.”

That was the motto of the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), known among its members as the “One Puka Puka” – the word “puka,” Hawaiian for “hole,” signifying the hole in the number zero. Many of the men were at or near Pearl Harbor on that date of infamy, when Japan bombed their home and their country. At the time, these men were loyally serving in the 298th and 299th Infantries of the Hawai’i National Guard. They guarded the shores, cleared the rubble, donated their blood, and aided the wounded.

Three days after the attack, their rifles were taken away, and they were confined to their tents. They were constantly under watch by armed soldiers, even when they went to the latrine. Their parents came from the country that attacked America. Even though they themselves were Nisei, second-generation Japanese American, American-born, they were treated with suspicion and fear. The next day the men were given back their rifles and resumed their duties, but many were shipped to the outer islands. The atmosphere of fear continued.

In 1940, the Japanese made up the largest ethnic group in Hawai’i, representing more than 37 percent of the territory’s population, and almost half of its vital workforce. After the attack, false rumors accusing Japanese Americans of sabotage and espionage were circulated. Some wanted to move the 158,000 Japanese Americans off Oahu, the main island, southeast to the small island of Molokai, home to a leper colony. Fortunately, civic and military leaders interceded, and when the economics and logistics were considered, the idea was abandoned. The Japanese Americans in Hawai’i would remain. However, some 110,000 mainland counterparts would not be as fortunate, eventually being forcibly removed into remote War Relocation Authority incarceration camps.’

In March 1942, the War Department had reclassified all draft-age Japanese American men as “IV-C” or “enemy aliens,” which meant that no Nisei could enlist in the armed forces. Still, many military officials were concerned that half of Hawai’i’s defense force looked like the enemy. By law, however, the Nisei who were already members of the National Guard could not be thrown out.1 In May, the 298th was placed in reserve, and troops from the mainland resumed their defensive positions.2 Yet the Japanese attack on Midway became imminent, and officials were concerned about how the Nisei soldiers would respond. They wanted them removed from the islands.

On June 5, 1942, at midnight, more than 1,400 Nisei from the Hawai’i National Guard boarded the Matson liner SS Maui. They were designated as the Hawai’i Provisional Infantry Battalion. Most of the men didn’t get to say goodbye to their families, and didn’t know where they were going. Five days later they landed in California. There, they were given their new designation as the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate).

To ensure that no mainlanders would see them, the Army hustled the soldiers onto various waiting trains, and hid them behind windows with their blinds drawn. Some soldiers thought they were going to an incarceration center. Instead, they went to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. From June to December they trained there.

The unit’s name itself – the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate) – indicated the War Department’s uncertainty concerning the Japanese American soldiers. Typically battalions are designated as first, second and third, and are part of a larger regiment.

But the 100th Battalion was an orphan, with no parent regiment, its status clearly marked by the designation of “Separate.” In January 1943, the 100th left Camp McCoy for Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

The men had been training for eight months, but still had no assignment.

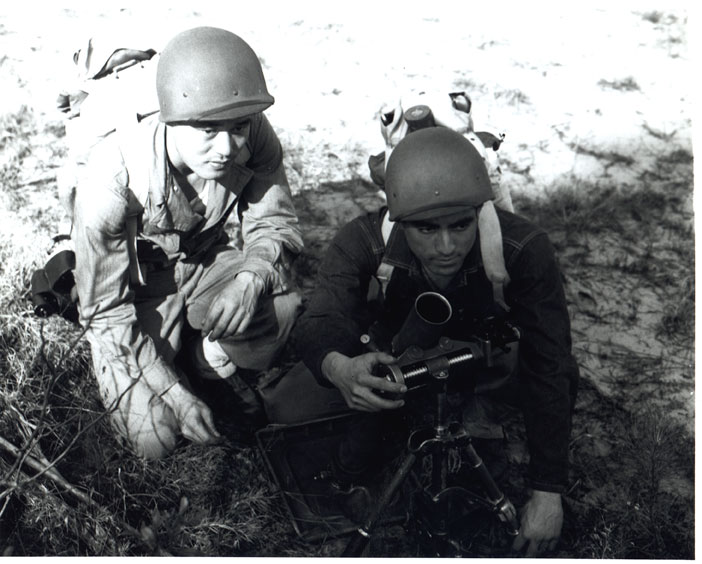

In May, the 100th participated in war maneuvers in Louisiana. Its performance in Louisiana and at Camp Shelby impressed army officials. Eventually its excellent training record and a steady stream of petitions from prominent civilian and military personnel helped convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the War Department to re-open military service to Nisei volunteers. These volunteers would later become the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who would offer the battalion to his generals and would receive an acceptance from General Mark Clark, later wrote:

“I will say about the Japanese fighting in these units we had: They were superb! That word correctly describes it: superb! They took terrific casualties. They showed rare courage and tremendous fighting spirit.”3

Footnotes

- 1The Selective Service and Training Act of 1940, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, established the protocol by which all males between the ages of 21 and 36 would register for the draft. An amendment by Senator Robert Wagner, passed by the Senate in that same year, guaranteed that any person, regardless of race or color, could voluntarily enlist and be inducted into either land or naval forces. Although in reality, this Act and amendment were often disregarded (Japanese Americans, for one, were later inducted only into the Army during World War II), they prevented military officials from immediately dispensing with those Japanese Americans who were currently within the National Guard ranks. See Morris J. MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1981), accessed on February 2, 2015, See also Lyn Crost, Honor by Fire: Japanese Americans at War in Europe and the Pacific (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1997), p. 14.

- 2“War is Declared,” 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans Education Center, accessed on February 2, 2015.

- 3Forrest C. Pogue, George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory (New York: Viking Press, 1963), p. 147.